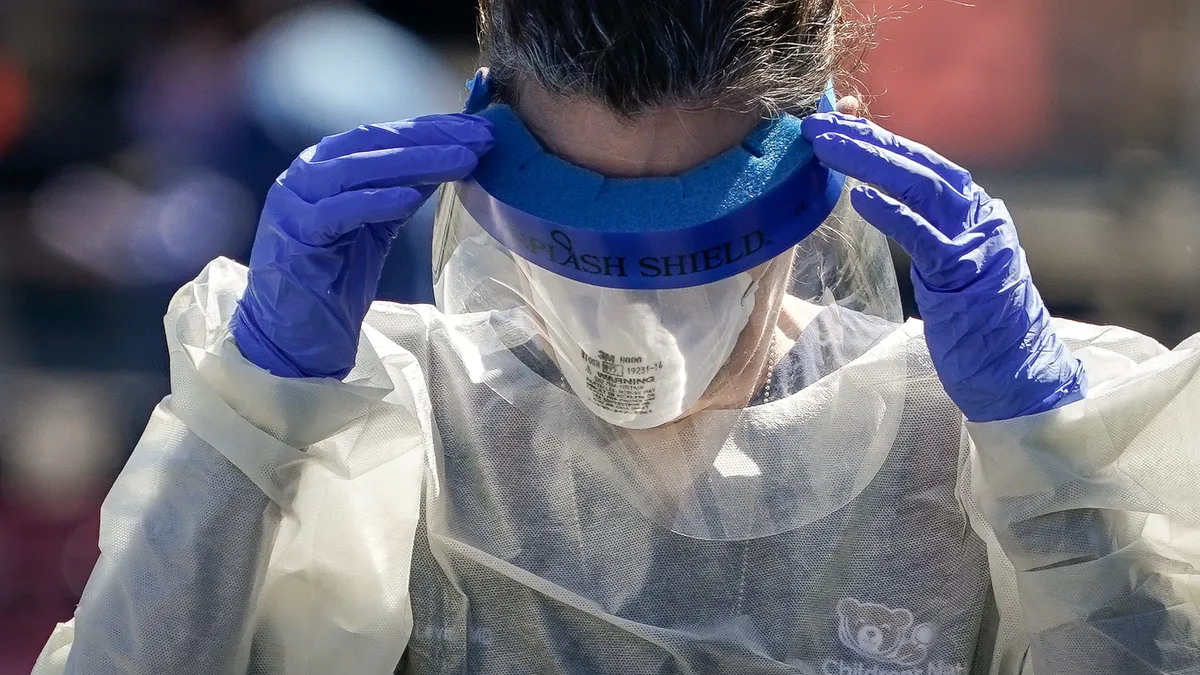

It's not unusual for Kimberly Mullen to get kicked, scratched, pushed or threatened during one of her shifts as a registered nurse in the telemetry unit at Kaiser Permanente's South Bay Medical Center in Los Angeles.

It's considered part of the job when dealing with patients who are sometimes confused, frustrated and feeling a loss of control in an unfamiliar hospital setting, she says. Still, she's thankful she hasn't fared worse, like one of her co-workers who was attacked by a patient's family member.

Mullen and millions of other healthcare workers nationwide are becoming accustomed to workplace violence, which can range from verbal abuse and threats to physical violence and even homicide.

The degree to which the pandemic has exacerbated the problem still isn't entirely clear, though a number of attacks already have occurred this year.

Yelling, name-calling and shouting obscenities are now daily occurrences, and "that did not use to be the case," said Hannah Drummond, an RN at HCA's Mission Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina.

Workers in the healthcare and social service industries experience the highest rates of injuries caused by workplace violence and are five times as likely to get injured at work than workers overall, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Those incidents have risen nearly every year for healthcare workers since the BLS began tracking them in 2011.

Sometimes they turn fatal. On average, 44 workplace homicides of private healthcare workers occurred each year from 2016 through 2020, according to the BLS.

Currently, there are no federal requirements healthcare employers must follow to protect employees from workplace violence, though the Occupational Safety and Health Administration offers voluntary guidance. A handful of states have rules for employers or laws penalizing offenders, putting much of the responsibility on individual hospitals.

Some nurses say the hospitals where they work have protected them effectively during the pandemic, citing measures like ongoing visitor restrictions and workplace violence prevention programs often spearheaded by labor unions or mandated by state law.

Others disagree, and say a lack of security, training and staffing challenges worsened by the pandemic are hindering their ability to provide timely, adequate care to every patient, resulting in patient and family frustrations that sometimes turn violent.

'Less and less resources to care for patients'

This comes as hospitals deal with unprecedented staffing shortages. They are unlikely to abate anytime soon as widespread stress and burnout spurs healthcare workers — especially nurses — to consider leaving their roles.

A quarter of U.S. hospitals reporting their data to the HHS said they faced critical staffing shortages in early January, according to the agency.

Drummond at HCA's Mission Hospital said a patient recently ended up striking one of her co-workers when staff couldn't get into the room with pain medication quickly enough.

"So much of the frustration that's taken out on nurses is justified, because each passing year we're getting less and less resources to care for patients," Drummond said.

So far this year, a number of attacks on healthcare workers already have occurred.

In one instance in late January, a patient's family member attacked an ICU nurse at Ochsner Medical Center's West Bank Campus in New Orleans, according to a statement from the system's CEO Warner Thomas.

Thomas now is advocating for state legislation to make violence against healthcare workers a felony as "hospitals grapple with an increase in disruptive or violent incidents in hospitals — many involving hostile visitors – adding further stress to the healthcare workplace," the CEO said.

In some states like Utah, lawmakers currently are considering legislation that would enhance penalties for assaulting healthcare workers.

Wisconsin already has a law that makes battery against certain healthcare workers a felony, though a bill moving through its legislature would extend that penalty to anyone threatening violence to a healthcare worker — similar to laws covering police officers and other government workers.

At the same time, there are no federal laws that directly address violence against healthcare workers, though last April the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act. The Senate hasn't passed it.

That legislation would mandate healthcare employers to develop and implement comprehensive workplace violence prevention plans based on guidelines that are voluntary from OSHA.

They would also be required to provide employees with annual training, keep detailed records of violent incidents and submit annual summaries to the federal labor department.

Currently, California has a law similar to that with guidance and enforcement coming through the state's OSHA department.

California and a handful of other states — such as Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon and Washington — also have laws requiring healthcare employers to run workplace violence prevention programs, according to the American Nurses Association.

Some provider groups like the American Hospital Association opposed the federal bill, saying hospitals already have specifically tailored policies to address workplace violence and a one-size-fits-all OSHA standard isn't warranted.

Verbal attacks on the rise amid COVID-19 frustration

Still, labor groups such as National Nurses United say a uniform, consistent and enforceable rule is necessary. The NNU opposes state laws aimed at criminalizing perpetrators of violence against healthcare workers, as those who do so are often vulnerable patients and locking them up does more harm than good, the union said in an emailed statement.

Nurses like Drummond say better staffing would allow nurses to give their full attention to patients and provide them with the best care possible while solving many of the issues that lead to violence. Having more ancillary staff like CNAs and security guards also would help, she added.

Earlier in her career, Drummond felt she had more time to have therapeutic conversations with patients and their family members.

"Now, I don't get to put that same time and attention into my patient care that I want to," said Drummond, who has been an RN for eight years.

How much of an impact the pandemic has had on violence against healthcare workers, which takes many forms, is still unclear, as the labor department's most recent data is from 2020 and the agency tracks workplace injuries and illnesses by looking at incidents causing days away from work.

Nursing assistants, registered nurses, licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses all had increases in days away from work in 2020, according to the BLS.

Nursing assistants had the highest number of days away from work among all occupations, which rose 2.5-fold from 2019 to 2020, the agency reported.

While some nurses have missed work because of COVID-19 infections, others have had to take days off to recover from violent incidents on the job. At the same time, nurses say frustration and misinformation around COVID-19 and the pandemic are spurring more verbal attacks in particular than they had experienced previously.

At the South Bay Medical Center where Mullen works, "frequent flyers," or patients who frequently return to the hospital with chronic conditions, often can be the most frustrated, and one such patient is known for hurling racial slurs at staff repeatedly throughout their shifts, she said.

However, a limited visitor policy throughout the pandemic has helped keep physical attacks at bay, Mullen said. The hospital still allows visitors for patients who are confused or dying.

Her hospital is covered by the state's workplace violence prevention law, though it's also a Kaiser facility with unionized nurses and a unique labor-management partnership with the hospital system.

Her hospital also has a dedicated workplace violence prevention committee that develops new techniques to ensure staff are safe.

One technique staff now employ involves putting a green card on the window of a patient who previously displayed violence or placing a green blanket on the patient.

That gives a signal to other staff, who may be food or environmental service workers, to be especially mindful if they haven't interacted with that patient yet.

The green blanket program started at one location before it was rolled out to all the other medical centers in Southern California, said Charmaine Morales, executive vice president of United Nurses Associations of California/Union of Health Care Professionals. The union represents over 32,000 healthcare workers.

In addition, panic buttons also have been installed on every computer at those facilities, Morales said.

Still, hospitals in other states without laws against workplace violence or unions pushing for more protections often don't have panic buttons or committees established to create new prevention methods.

Morales says a national regulation like the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act would help, "versus leaving each state to decide what to do."

However, "just because you don't have a law in place, doesn't mean that you should not do the right thing to protect workers physically and mentally," she said.