Justin Lugar is a Roanoke, Virginia-based attorney with Woods Rogers. As a former Assistant U.S. Attorney, Justin led the Affirmative Civil Enforcement team in managing active fraud investigations. He may be reached at [email protected].

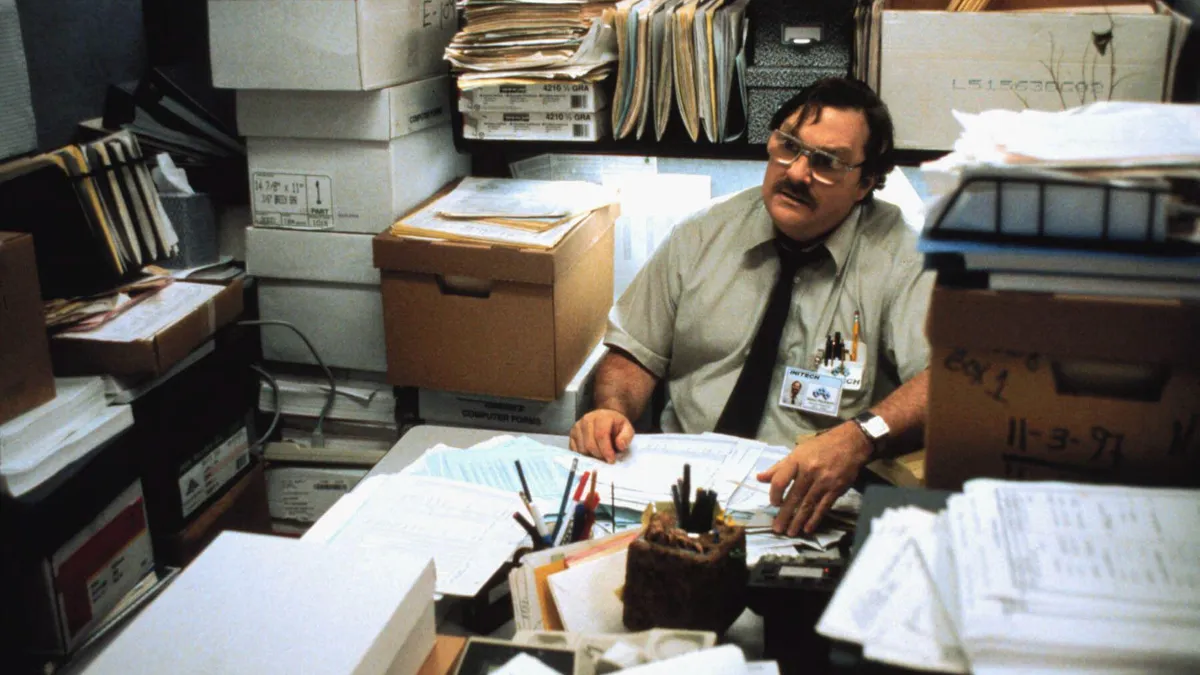

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the release of Mike Judge’s cinematic magnum opus, “Office Space,” and on my anniversary viewing, I realized the film provides us with much more than comedic relief from the corporate hustle. It also presents important lessons about how to handle whistleblowers and warns of the consequences of corporate action — or inaction — that can lead to disaster.

Meet Milton

The movie takes place at a suburban tech company called Initech. There are numerous plot lines, but at the story’s core is the tale of an employer that has hired a pair of consultants, known as “the Bobs,” who have been retained to increase productivity and cut waste. Through their review, Initech learns that one squirrelly employee, Milton, was laid off years ago. The problem? No one bothered to tell Milton he was let go. By some stroke of luck (for Milton, at least), he was never removed from the payroll and continued receiving his paycheck. The Bobs, proud of their ingenuity and creative thinking, tell Initech they’ve “fixed the glitch” in payroll. Rather than tell Milton the unfortunate news, the Bobs tell the employer “it’ll just work itself out naturally.”

Cue Milton, whose slow progression to a basement office through passive management and lack of communication leads to a “bet the company” situation. I will not spoil the film, but rest assured, Milton’s repeated warnings, questions and complaints go unheard and unheeded, ultimately resulting in disaster for Initech.

Consider your own office

As one who has investigated, prosecuted, defended and filed whistleblower claims, I can assure you that Milton’s story is not unique or out of the norm.

While I’ve yet to see any glitch in payroll akin to Milton’s situation, I have often seen companies miss early opportunities to engage with employees long before they contemplate blowing the whistle. And importantly, even if there is no real whistle to be blown, there are affirmative steps HR and legal departments can take that both provide an opportunity for an employee to be (and feel) heard on an issue and alert the company to any possible issues that it may need to deal with to avoid the genuine problems that may arise.

Challenge assumptions

Press the “reset” button on everything you think you know about whistleblowing and the term “fraud.” In civil fraud, an individual or corporation need not have the type of intent required that is generally associated with fraudulent or dishonest acts that we hear about in the news. Instead, under the False Claims Act — the whistleblower’s oft-used statute — one may have actual knowledge that certain information communicated is not accurate, one may act in deliberate ignorance of the truth or falsity (a sort of willful blindness to the truth or falsity) of a statement, or one may act in reckless disregard of the truth or falsity of material information.

This sliding scale of knowledge and awareness should reorient HR and legal departments because the standard for showing knowledge is relatively low. Reckless disregard for the truth or falsity of information can mean that someone failed to verify a key statement or possessed some information that would make most people question the accuracy of a statement the company might make.

The bottom line is that HR and legal departments would be well-served to disregard preconceived notions of what “fraud” actually is under the law and reorient their thinking to recognize that what the law calls “fraud” often occurs without bad motive or intent. The phrase “trust but verify” takes on a whole new meaning in the context of civil fraud.

Communicate effectively

Legal and HR must listen, hear and then communicate effectively (e.g., be prepared to share information) with the employee about the concerns raised. It is essential that an employee who reports concerns — no matter how absurd some complaints might seem — feels heard. An employee does not feel heard unless they receive feedback or see responsive action. That does not mean the employer must acquiesce or cede control to the employee. Still, it must meaningfully interact with the employee to prevent escalation or the perception that the employee has been ignored.

Many times, at least in my experience, putative whistleblowers possess compartmentalized knowledge. For instance, I have seen billing specialists in healthcare companies file complaints claiming that a provider was upcoding billing to Medicare/Medicaid/Tricare. Unbeknownst to the whistleblower billing clerk, the healthcare company never submitted the alleged up-coded bills before verifying the charge was correct by reviewing the medical records. For some bills, the upcoding was perfectly appropriate; in other cases, the bill was revised before submission. Ultimately, the government determined there was no false statement even though the whistleblower was convinced that all the supposed up-coded bills were submitted.

If your potential whistleblower has incomplete information, equip them with the information to prevent the complaint from ever being lodged.

Document everything

Once you catch wind of a potential problem, real or contrived, document everything. Take contemporaneous notes of every encounter with your potential whistleblower. If you share institutional information with the employee, memorialize it. If you take steps to investigate allegations, even if they are ultimately deemed unfounded, document every step.

Through documenting in real-time, you are creating a record that should demonstrate to the government (if the complaint gets that far) that the company was responsive and took proactive steps to address the allegations.

If in doubt, reach out

Reach out early to trusted counsel to help ferret out any possible allegations. No one wants to be accused of fraud, but the only thing worse than a false accusation is the decision to ignore the problem and hope it goes away — as Initech learned the hard way.

If there is a problem, self-disclosure can be a viable strategy (in the right circumstances and only after seeking experienced counsel from an investigations attorney). These are big decisions, and the longer an institution sits idly by, the more time a whistleblower (or the government) has to build their case. So, get busy and get good outside advice.

The moral of the story is to engage. Do not follow the path of the Bobs in “Office Space.” Just as Milton’s payroll glitch did not just work itself out, neither will a potential whistleblower situation. Engage strategically and with purpose so that the company, not a Milton, takes control and “works it out.”