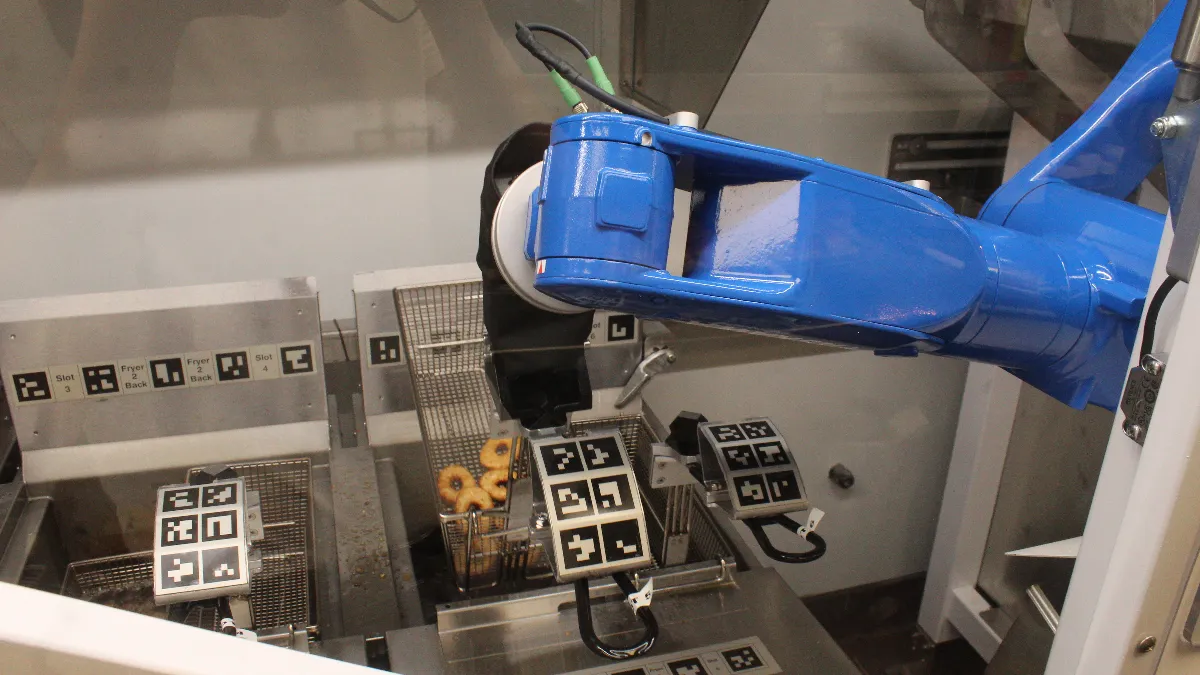

Oil hissed as the White Castle fry cook lowered a basket full of chicken rings into the vat. Next, the cook pulled a basket of fries out of the fryer, letting hot oil drain off for a moment before dumping them at the station where fries are packed and served.

From there, the cook continued to load, drop and pull fryer baskets. It’s a tough job — repetitive, hot, and greasy. But this cook doesn’t pause or flinch at a splash of grease because, instead of skin and muscle, this cook is made of cast aluminum. Called Flippy 2, the robot worked with a mechanical whirl, unceasing, unbothered by the heat and the noise.

Flippy 2 is the second iteration of Miso Robotics’ fry station robot, and a refinement of early attempts to build a labor-saving machine for QSRs. The technology looks to build a cook that never gets sick, never undercooks an item and is never a “no-call, no-show.” Miso’s robot could serve as a two-in-one solution for the restaurant industry, which is the only major business sector to have wage growth outpace inflation, and is struggling to reach pre-pandemic staffing levels. The product is resonating with major chains: White Castle will deploy Flippy 2 in nearly one-third of its stores by the end of 2023. White Castle is the earliest adopter of Miso’s technology, but Wing Zone has committed to deploying Flippy 2 in all future restaurants, and Chipotle is testing Miso’s chip-making robot as well.

Automation is easing White Castle’s labor pressure and improving efficiency

The Mokena, Illinois, White Castle is the third of the chain’s stores to install Flippy 2. It’s also short-staffed. Diana Williams, the district supervisor responsible for 14 White Castles straddling the border between Illinois and Indiana, said the location has faced fluctuating employment levels since the start of the pandemic. In May, the store had 32 employees, about 8% below Williams’ desired staffing level of 35 workers.

Traditionally, the fry station required two employees to oversee it. One of the workers’ main tasks was just to handle the baskets in the boiling oil.

“The one that's always managing baskets and dropping frozen product is really just always in front of that fryer. That's the work environment. A very, very challenging work environment,” Mike Guinan, White Castle’s vice president of operations and services, said.

Flippy 2 frees up workers who would normally be responsible for the fryer to work at what Guinan refers to as the “hospitality door,” a door next to the drive-thru window where workers can carry food and drinks out to cars and greet customers. This, in turn, alleviates pressure on the drive-thru employees, who must take and collect orders, make drinks, hand off food and attend to customers at the window and over their headsets. By reallocating labor from the fryer to the drive-thru, White Castle has improved drive-thru speed of service.

“We're seeing somewhere between 15% and 25%, faster [order] times,” said Jacob Brewer, chief strategy officer at Flippy 2’s parent company Miso Robotics. “And traditionally, a hang up is the fry station. You're often waiting on fries, even if it's one, two or three seconds. Three seconds out of a 90-second order is still meaningful.”

Miso refined the robot to mitigate training needs

An earlier version of Flippy was less efficient from a labor-saving perspective, Brewer said, because workers had to fill the fryer basket before the robot picked it up. Operational testing, as well as testing at Miso’s Pasadena, California, laboratory, allows the robotics company to continually refine the design and software that powers Flippy 2.

“Masters and PhD roboticists and software engineers will interact with something far different than [restaurant workers],” Brewer said. “If you want to see if something really is tough, put it in a restaurant.”

Brewer said high turnover in restaurants also drives Miso to improve and simplify its user interface.

“What we didn't plan for is once we trained everyone, turnover is still 100% [at many restaurants], which means everybody is leaving every year,” Brewer said. This turnover figure wasn’t specific to White Castle, which he said had some of the lowest turnover among QSRs. In light of the industry’s turnover rates, Miso designed Flippy 2 so it is intuitive to use and easy to train workers to interact with. Employees need to feel like the robot is a productive team member, he said.

The Flippy 2 arm moves faster than the original Flippy, Brewer said, not because it’s necessary to speed up throughput, but because slower movements led workers to feel the robot was sluggish and inefficient.

Williams said Flippy 2 works well in the kitchen, and has integrated into the operations at White Castle smoothly. In Mokena, one worker feeds product into the machine, while a second, who previously would have been assigned to handle baskets, expedites drive-thru orders and interacts with guests.

Robotics costs can be competitive with wage costs

White Castle’s configuration of Flippy 2 frees up one worker for redeployment from the fryer, making the robot something of a replacement for an individual worker. But how does the cost of a worker compare to the cost of a robotic arm across a full year’s operations?

Miso charges restaurants a $5,000 installation fee for Flippy 2, and a $3,000 monthly service charge, Brewer said. That cost structure is intended to make it easier for franchisees to adopt Flippy 2. Brewer said this cost – $41,000 per unit in the first year and $36,000 each subsequent year — is lower than the equivalent labor costs of a staff member manning the fryer.

A restaurant with three dayparts, operating the fryer during two hours on peak and one hour before and after peak, has someone dropping and pulling baskets at the fryer station for 12 hours every day. Stretched across 365 days and multiplied by the $15 hourly wage that is increasingly prevalent in major markets, that adds up to $65,700 in raw wages. For a restaurant with two dayparts, the same assumptions yield about $44,000 in wage costs. It is, in Brewer’s telling, a math argument.

“You're cleaning up,” Brewer said. “You're getting a killer ROI from day one.” Brewer added that the choice to reallocate labor, as White Castle says it is doing, or to cut jobs is up to the brands themselves.

But a closer look at labor market data reveals a more complicated equation. Fast food cooks in the U.S. earned on average $11.63 an hour, the lowest wage of any job class in food preparation and serving-related occupations, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. This would yield a wage cost of $50,939 for a restaurant open for three dayparts, closer to Flippy’s first-year costs. A restaurant open through just two dayparts would see average wage costs for a fry cook around $33,959, just below Flippy 2’s cost in its second year of operations.

The hourly wage at which it becomes cheaper to install Flippy 2 than to employ a fry cook for three dayparts is $9.36 in the first year, and $8.21 in subsequent years. For two dayparts, the break even point for wages compared to Flippy 2 fees is $14.04 in the first year and $12.32 in following years.

But this comparison of hourly wages and costs doesn't account for expenses that vary on a store-by-store basis. For example, installing Flippy may cause a restaurant to pause operations for a day or two, or require kitchen renovations to make space for the robot. Restaurants would also need to train staff on how to interact with Flippy. But Flippy 2, as Brewer said, does not come with some of the more costly aspects of labor, like training workers to operate the fryers, which can add up for brands like White Castle that cross-train their employees so they can fulfill any back-of-house role.

Robotics could shape the restaurant labor market

Major publications have argued since at least 2015 that wage increases would spur automation in fast food. Miso’s deals to bring robots to hundreds of units in the next few years, and the number of robots working the floor at the National Restaurant Association Show, suggest a growing swath of the industry is embracing automation. Recent surveys have indicated restaurant operators are hungry for technology that can reduce inefficiencies across management, back-of-house and front-of-house roles.

Brewer also touted Miso’s crowdfunding, totaling more than $50 million raised from 18,000 shareholders, as indicative of a larger acceptance of automation in restaurants.

“People get the product, people get the problem,” Brewer said.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, wages were growing steadily in foodservice, according to the BLS. Employment in foodservice grew steadily too, peaking at 12,360,000 workers in February 2020. Both fell in the months that followed, according to BLS data. Since then, foodservice wages have outpaced broader inflation, and the growth in compensation has exceeded the recovery in employment. The number of foodservice workers, about 11,566,000 in April 2022, lags behind pre-pandemic peaks by more than three quarters of a million workers.

Rising wages haven’t drawn workers back into foodservice fast enough for many operators, who have cut hours, simplified menus and leaned into operational efficiencies. Now, a number of chains are betting on back-of-house automation to solve operational problems — including White Castle.

“At the end of the day, we want to have Flippy in every Castle,” Guinan said