Jonathan Segal is a partner with Duane Morris and managing principal of the Duane Morris Institute.

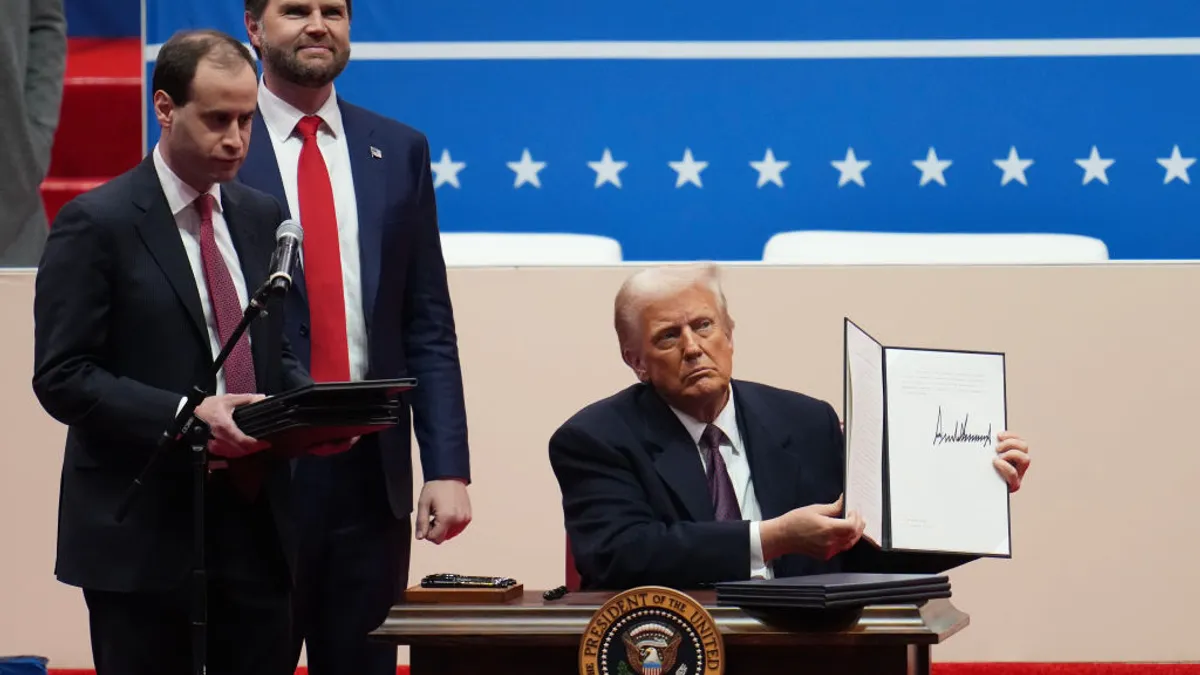

As you undoubtedly have read, President Trump has ended DEI in the federal government and has revoked executive order 11246, which required affirmative action by federal contractors for women and certain minority groups. But President Trump’s executive order “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity” also takes aim at private-sector DEI.

Section 4 of the executive order is entitled “Encouraging the Private Sector to End Illegal DEI Discrimination and Preferences.” To achieve this goal, President Trump has directed all federal agencies, with the assistance of the U.S. attorney general, within 120 days of the executive order, to:

- Identity the most “egregious and discriminatory DEI practitioners;”

- Develop a plan or specific steps or measures to deter DEI programs or preferences that constitute “illegal discrimination or preferences;” and

- Establish strategies (including litigation) to encourage the private sector to “end illegal DEI discrimination and preferences.”

Contrary to some reports, the executive order does not attack all DEI initiatives. It purports, by its plain words, to attack only DEI practices that are illegal.

We already are experiencing a tsunami of challenges to DEI programs, including an increase in “reverse discrimination” claims alleged to be a product of unlawful DEI initiatives. This trend will be exacerbated by the executive order.

Trump’s executive order is a clarion call for employers to review their DEI practices now.

The nuance of “illegal DEI”

Your audit should begin with practices that are clearly unlawful. By way of example only, quotas, set asides, and racial, gender and other preferences are unlawful.

But employers must do more than focus on programs that are unlawful on their face. Employers also must evaluate programs that are not illegal per se, but which may encourage illegal conduct. For example, some companies establish “aspirational goals” to improve workplace diversity metrics. Such goals may be seen, and therefore challenged, as de facto quotas. The challenge will be even stronger if leaders are evaluated and/or compensated on their efforts to achieve such goals.

Further, it is not only specific employment policies and practices that employers must consider; employers also must look at the culture. For example, employers or training agents that classify and refer to employees as “privileged” or “unprivileged” (oppressors and oppressed) based on their race, sex, religion, orientation or other immutable characteristic all but invite attack by the federal government or private plaintiffs.

Look also at the meta message of your programs, too. For example, many DEI programs include implicit bias training. Is the message of the program evenhanded? Or does it suggest that White folks and/or men are the primary perpetrators of implicit bias?

And let’s talk about “woke” language, which often is conflated with DEI. Yes, we need to be sensitive to the words we use and be thoughtful about using words that are as inclusive as possible. But common sense needs to be considered, too. What do you call an employee who is publicly “corrected” for saying “pregnant woman” rather than “birthing person?” A whistleblower.

Of course, the process of auditing one’s DEI initiatives is not without legal risk, particularly if unlawful or high-risk DEI practices are discovered. Employers should consider the potential benefits of attorney-client privilege when conducting the audit.

Further, the process of making changes is deceptively complex. When taking corrective action, employers need to avoid, where possible, suggesting that any prior practice may have been unlawful. Focus, for example, on making the practice “even more inclusive.”

Paving the way forward for DEI

Of course, employers should do more than play defense. Employers must look at what specific steps they can take to strengthen their position on diversity initiatives that are not unlawful or high-risk. For example, make sure diversity is defined broadly (beyond protected characteristics). Talk about other kinds of differences that may affect a worker’s experience, such as skills, experiences and perspectives. It’s hard to argue that diversity is about anything other than protected factors if you focus only on protected factors.

And don’t forget to train managers on hiring and promoting. In the absence of such training, some managers inevitably will provide unlawful preferences in order to increase diversity.

For some, the legal risks of continuing a diversity initiative may seem too high. Isn’t it safer to jettison DEI programs altogether? The simple answer is an unequivocal “No.”

The business benefits of diversity are stronger today than they were yesterday as the diversity of the pool of qualified talent increases. Inclusion of diversity is necessary to hire and retain top talent.

Further there are legal risks in cutting back your DEI programs unnecessarily. What is the message you are sending to your workforce, business partners and consumers? Just as plaintiffs are challenging overbroad DEI initiatives, members of the plaintiff’s bar already have made clear that they intend to argue that pulling back on DEI reflects hostility based on race, gender, and other factors.

There is risk regardless of what we do (or don’t do). So we might as well do what is right. And, from my perspective, that means continuing to focus on the inclusion of diverse talent but without unlawful preferences, exclusions or messages.