LAS VEGAS — What if you could use your co-workers’ Hogwarts Houses to be an effective leader?

Ned Herrmann’s “Whole Brain” model, which executive coach Lei Comerford broke down for attendees at the Society for Human Resource Management’s 2023 annual conference, is kind of like that.

The four types

Late “creativity researcher” Ned Herrmann pioneered a model that comprised four types of thinking: analytical, experimental, relational and structural. Comerford’s highly interactive session on Monday — which drew wry laughs, little cackles and gentle ribbing from an otherwise demure crowd — left a colorful impression on SHRM attendees.

“Spreadsheet” people, aka analytical thinkers

The analytical thinkers love to analyze and quantify, Comerford explained. This type of thinker — or the state when an individual embodies this “rational” self — is logical, critical and realistic. They like numbers and like to crack open the mechanics of systems.

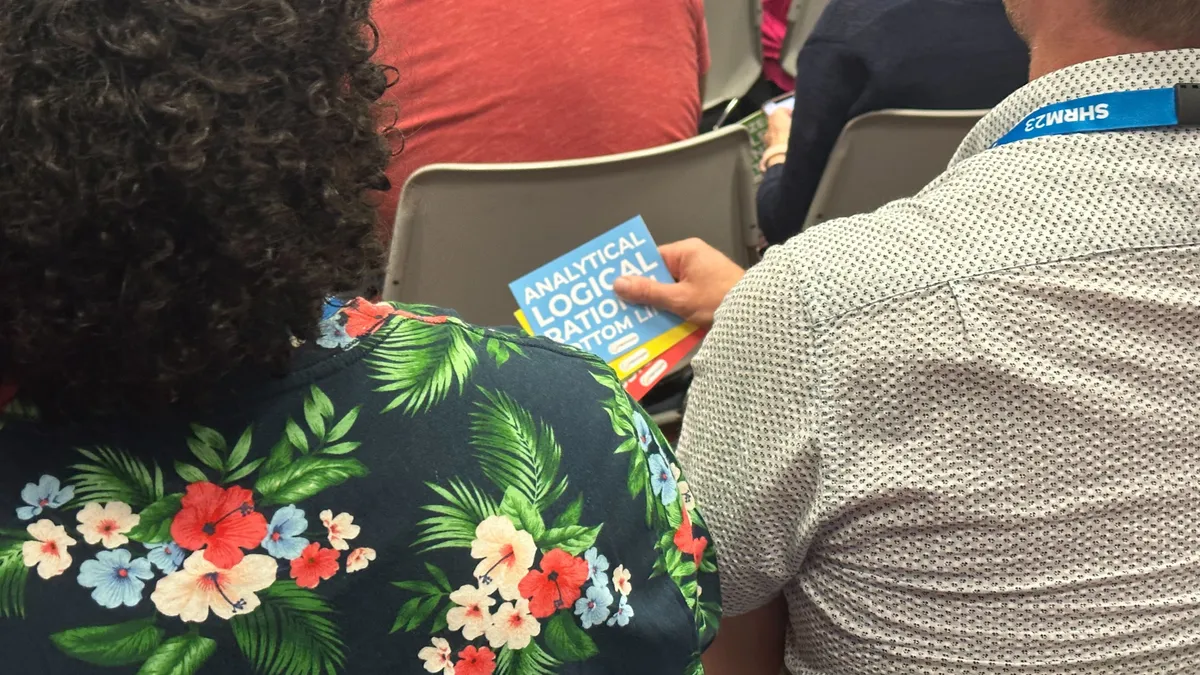

Simply put, these individuals are “spreadsheet” people; conference attendees who copped up to their love of data waved their cool blue-hued cards. Each attendee was given a tearable sheet of four cards for the each type, and were asked to hold up a color to signify a type of thinker.

Backup planners, aka structural thinkers

Structural thinkers, or those who are embodying the “safekeeping” self, take preventative action, Comerford explained. They love to establish procedures and get things done.

People who felt they fit into this category of reliable, organized and neat workers held up their kelly green cards.

This way of being, it seems, entails a backup plan for the backup plan. These are likely the “compliance” people, Comerford added — the ones who love standard operating procedures.

Sensitive types, aka relational thinkers

People from the blue and green camps — including Comerford, who considers herself a structural thinker — had a laugh at the red quadrant’s expense. She painted relational thinkers as those sometimes overzealous, maybe a little too gregarious co-workers who are deeply invested in their colleagues’ feelings.

In a way, it was clear that Comerford had a bit of what Gen Zers call “the ick” regarding these types of thinkers; they’re sensitive to others, they like to teach and they’re the type to touch their colleagues shoulder in an encouraging manner.

They’re emotional, expressive and supportive; nevertheless, Comerford reassured attendees that they could be a relational thinker even if they weren’t overly sentimental or touchy-feely.

Innovators, aka experimental thinkers

And last were the experimenters — the innovators who have their heads in the clouds and perhaps need a bit of grounding from their greener, structurally-minded co-workers.

These workers love to imagine, speculate and infer. They like surprises and play, Comerford explained. The yellow cardholders self-identified with being the rule-breakers and the risk-takers.

“Get a grip for just a minute,” Comerford ribbed, appealing to the more practical thinkers in the audience, who were expressing open disdain for experimental thinkers. “This is something that people actually enjoy.”

What if you’re more than one?

Unlike some other personality models, Comerford said the Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument, or HBDI, gives people the room to feel less “pigeonholed.” (Consider the way some Harry Potter fans have expanded the Hogwarts archetypes; several decades removed from “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” fans have taken on mutant monikers like Slytherpuff and Griffinclaw.)

It’s for this reason that Comerford asked SHRM attendees to rank the quadrants within themselves. It’s not so much about fitting into one category, but recognizing that one way of being may be more dominant.

Like the Sorting Hat, which seeks to tap into an individual’s essence, Comerford made the careful distinction that categorization should reflect natural inclination — and not “competency or skill.” For example, while she is very capable of organizing data, she said, “spending a day in spreadsheets” would drain her energy.

Why should employers care about cognitive differences?

It actually makes everyone’s life easier, Comerford noted. She told an anecdote where a conversational performance check-in was lost on a boss because he was an analytical thinker. (Her company at the time used the HBDI model.) She came back to her colleague with charts and data instead of bulleted talking points. Years later, when she was set to resign, Comerford said this coworker was the first to tell her he would write her a letter of recommendation. The lesson? That is the degree to which considering employees’ different cognitive styles can transform workplace relationships.

Within the diversity, equity and inclusion space, knowledge of neurodiversity provides insight into workplace culture and productivity — including through a disability lens.

For one, neurodivergent people and those with cognitive disabilities experience greater exclusion within the workplace. Last year, a report by TextHelp and corporate inclusion network Disability:IN suggested that most neurodivergent people (61%) experienced stigma or felt misunderstood in the workplace.

A lackluster sense of belonging can be a pipeline to disengagement, which can lead to a drop in productivity, and ultimately, attrition. Beyond retention issues, employers can miss out on highly qualified talent on the front end. The same joint report with Disability:IN suggested that 1 in 3 neurodivergent people experience difficulty during the job search and recruitment process. Notably, this report highlighted some common disabilities, and the challenges they present along with some of their underrated benefits.

Workers with autism, for example, may need extra support with time management and scheduling, concentration and the social aspect of the workplace. In turn, folks with autism can often shine in the workplace due to their special interests — including literature, computation and other areas that often relate directly to work. The report also suggested that attention to detail and fresh innovation are also autism superpowers.

Similarly, while folks with dyslexia may have challenges with literacy, cognitive function and social self-esteem, their strong suits can include an entrepreneurial spirit, advanced visual-spatial skills and storytelling, the report suggested.

How do employers bridge the neurodiversity gap?

Examples given in the 2022 report included simple fixes, such as dedicated, quiet workspaces and more freedom or options around how workers receive information. Survey respondents also reported neurodiversity awareness training as an ideal solution to addressing the gap.

In many ways, Comerford’s session demonstrated a simple way for employers to be more brain-inclusive. It underscored that an open workplace discourse about thinking differences can be as straightforward as asking employees how they think, how they best receive information and how they’d like to present it.

The quadrant model is “sticky,” Comerford said. It’s “simple to learn, but far from simplistic.”