Editor’s note: Emilie Shumway is an editor for HR Dive. This column is part of her new series, which will explore how our personal lives intersect with the workplace. She can be reached at [email protected].

As my colleague told me when I suggested this column, to say Severance provides a good example of HR mistakes would be “putting it mildly.” Fair enough. The psychological thriller from Apple TV+ takes place in an alternative present or near future and centers on a set of workers at Lumon Industries, a mega-corporation with a purpose that never becomes quite clear in the first season.

The workers in question have voluntarily undergone a surgical process called “severance,” through which their personal, outside-of-work memories are separated from their professional, at-work memories. Functionally, this means their “innies,” or at-work selves, are left to wonder what their personal lives are like, including whether they have partners or children; their “outies,” or out-of-work selves, know they work at Lumon but have no idea what they do all day.

Assuming we can all agree that HR shouldn’t ask employees to undergo any ethically dubious surgeries (or any surgeries at all, for that matter!), the show’s satirical portrayal of corporate life still draws on some real practices that aren’t quite eradicated across the HR space, despite major strides. (Note: While I’ve tried to exclude any major spoilers, this may be one to bookmark and return to later if you want to go into the show completely fresh.)

Don’t reward with trinkets

Look — everyone likes a little gift from their employer once in a while, whether that’s a box of chocolates or some company swag. But HR brings on eyerolls (and no little disdain) when it uses trinkets as a carrot, a means of incentivizing workers to push a little harder, without offering more meaningful rewards alongside them.

In an early episode, main character Mark Scout receives a complimentary gift card to a local bar and grill from Lumon after he sustains a minor injury at work. Another worker keeps a mug of hard-won finger traps on his desk.

Trinkets can be more than physical items as well: In one particularly surreal scene, an employee reaches a quota that earns her a “five-minute music dance experience,” for which she is allowed “one genre and one accessory.” (She picks a maraca and “defiant jazz,” naturally.)

Trinkets, trifles, tchotchkes: given too much emphasis, all only serve to reinforce the heavy load a worker is carrying for far too little reward. Lumon Industries has its own dark corporate underworld, but for some workplaces that load might be too many hours, a toxic manager or an inability to nurture one’s passion projects. A curated candy box might be nice to receive come the holidays, but it won’t make up for a stifled work life.

Don’t turn the workplace mission into a religion

This one can be tough, especially with studies emerging all the time that workers want to identify with their organization’s mission and values. HR wants employees to develop a strong sense of identification and belonging with the workplace — a pride and belief in its goals — and for good reason. Such feelings foster engagement and can lead to better retention.

But boundaries are important. Lumon provides employees a set of “compliance handbooks,” written like religious texts: “Whatever your task, dear worker, see that you endow it with love,” reads one excerpt. “Endow in each swing of your axe or swipe of your pen the sum of your affections, that through me they may be purified and returned. No higher love may be found than this.”

In one episode, the workers take a trip to the office’s “perpetuity wing,” a revered hall featuring wax figures of the founder and early leaders of Lumon, along with their stirring quotes. In another, the severed workers’ supervisor subjects them to a hymn in honor of Lumon’s founder.

Granted, these actions are especially weird for a workplace. But it’s worth asking whether your own company may be asking for unconditional devotion. Are workers given the space to disagree with policies and even provide honest feedback on the mission, or is this seen as sacrilege? Are there mandatory “fun” chants, extraneous committees or rituals? Employees need the space and power to opt out when they disagree.

Remember that mental health is not toxic positivity

More workplace attention is being paid to employee mental health, and it’s high time. Workers bring their minds to work, along with their strengths and foibles. Some days are better than others, and even in work relationships that are healthy and open, we never really have full access to what someone may be going through.

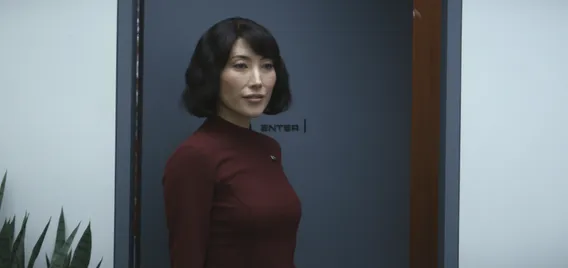

Lumon Industries has a solution for tough times: Send workers for a session with the wellness counselor, Ms. Casey. What then unfolds is a hilarious litany of positive facts about the worker’s “outie,” recited in Ms. Casey’s calming, ASMR-inducing voice: “Your outie is generous. Your outie is fond of music and owns many records. Your outie is a friend to children and to the elderly.”

For workers having a tough time, it may be tempting to apply a balm of positivity: “You’re doing a great job.” “You’re such an asset to the company.” While recognition is good and plays an important role, it’s no substitute for mental health resources. Employees need to know they can take a break if they need one, and they need access to options like counseling (of the non-Ms. Casey variety).

Note that work-life balance does not mean work-life severance

HR has been attempting to navigate the work-life approach for years. While the idea of achieving balance is ideal — and employees need to be able to clock out — some have questioned the notion. Many advance “work-life blend” or “work-life integration” in its place: A policy that gives workers space to run necessary errands or make appointments whenever they need to, without use of limited PTO, as long as the work gets done.

Integration, you’ll note, is the opposite of severance.

Throughout the first season of Severance, it becomes clear that some severed workers chose the procedure to escape painful circumstances in their personal lives. They are responding to a truism that work can often provide a helpful routine, a way to shut off your emotional brain when you need a break from grief or trauma. But this flow state we fall into cannot be sustained for eight uninterrupted hours a day, five days a week — nor would we want it to.

In a late-season episode, one Lumon worker discovers he has a son outside the office, shattering his contentment in his severed state; he feels deprived. HR pros have told me stories of poor management from supervisors who never bothered to learn their kids’ names, or even if they had kids. Leaving at 5 p.m. to “return” to one’s life is not the work-life balance that seems to fulfill us.

Whatever you call the work-life equation, work and life happen simultaneously. Sometimes that means leaving at 3 p.m. for a soccer game and finishing the spreadsheet after. Sometimes that means a diversion in Slack about a new show you’re watching.

And it always means understanding we’re full people at work — not two divided selves.